Dear Reader,

Thank you for signing up for my newsletter. Beginnings are scary, but I am glad you are here.

If you have thoughts to share, write to me at poorna19@gmail.com. If you like what you read, do share the sign-up link with your friends.

Happy weekend!

Poorna

To the Wonder

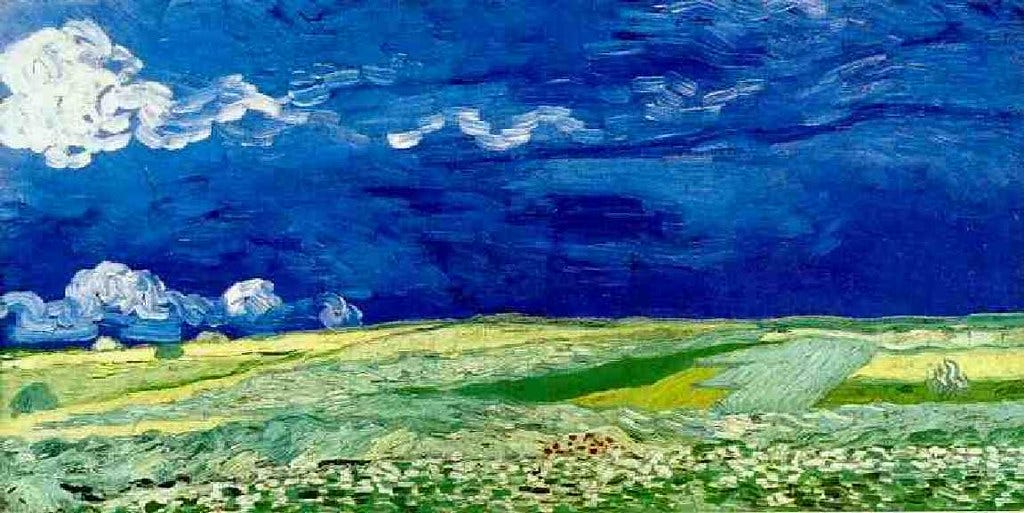

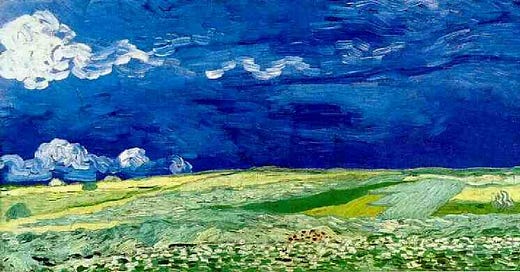

There are places on Earth where the sky is bigger. I have seen them. The Rann of Kutch. Roads winding towards Colorado’s Collegiate Peaks. The Himalayas. Before you tell me it’s a matter of proportions, that the sky does not enlarge, I want to insist—it does.

These days, I live with a smaller sky. Of course, it’s beautiful in a way, but there’s nothing vast about it. From the fifth floor, I see the way this sky’s bottom edge is rimmed with uneven crests of green. On its left, there’s a water tank from the ‘80s shaped like a spaceship. On its right, a tall glass building that remains blindingly lit through every hour, so night no longer means darkness. This is my familiar sky. And I know its measurements.

There’s something peculiar about scale. Largeness strikes wonder. Sure, there’s beauty in the details, and bigger does not mean better. But there’s a truth I recognise about myself—I dream of big skies.

Think back to when you saw the most stars in the open. It was likely a quiet place, where the air was thin and smelled, if not pleasant, different. And the sky—it was big. Bigger. In it, you saw a mess of stars, more and more, appearing and disappearing as you tried to connect them. You might have felt insignificant.

Comparing your smallness to the grandeur of the universe brings its own kind of awe. But there’s another feeling, I think, which is harder to describe—when against that largeness, we feel infinite. Romanticism is filled with this communion. William Wordsworth, in “A Night Piece,” writes:

The sky is overspread

With a close veil of one continuous cloud

All whitened by the moon, that just appears,

A dim-seen orb, yet chequers not the ground

With any shadow—plant, or tower, or tree.

At last a pleasant instantaneous light

Startles the musing man whose eyes are bent

To earth. He looks around, the clouds are split

Asunder, and above his head he views

The clear moon and the glory of the heavens.

…

At length the vision closes, and the mind

Not undisturbed by the deep joy it feels,

Which slowly settles into peaceful calm,

Is left to muse upon the solemn scene.

Wordsworth observes this “overspread” vision, trying to account for its every detail. But he realises he cannot. For the sky “still deepens its interminable depth”; all he can do is stay with it. And in his watching, he makes that sky vaster still.

A thing of wonder—whatever its size—redraws the limits of our understanding, expands them. Often, we cannot find the right words to describe why we are struck and what we feel. A wondrous thing disrupts our sense of continuity because it is, by definition, more than ordinary.

Large things of wonder—the sky, the sea, a colossal monument—magnify this uncertainty. It’s a kind of doubling. There’s the physical experience of vastness—for Wordsworth, a moonlit sky impressing itself upon his being. And then, there is the cerebral one—the way he cannot express exactly what has overcome him. He musters only, “the mind/ Not undisturbed.” For him, that disturbance is joy.

Sharmistha Mohanty begins her fascinating poetry collection The Gods Came Afterwards with an incantation:

Make broadness broadness

from narrowness

Lead lead us

We see nothing

behind nothing ahead

These worlds are broad above

beyond our knowing

The great river plains open and descend

slowly from west to east

beyond our knowing

Us

…

Broadness open for

us us

Unharness our days

Let all boundaries be distant

so we can wander far

in our unknowing

For Mohanty, the encounter with something immense leads to a place of widened knowledge, where we forego the rules of linear understanding and are forced to lose compass. “Unharnessed,” we don’t just recognise that river plains are vast; in a sense, we become them, too.

In the last five months, I have spent almost all my hours in my room. I work here, sleep here, watch Netflix and eat snacks here. When I look out, I anticipate my personal sky; the same window frames the same sky, mapped in the same dimensions. Sheltered as I am from disease by these walls, I confess to craving broadness.

Maybe that is my failing—not being able to spot the wonderful within the familiar. But here’s the thing: wonder does not exist without surprise. The word ‘surprise,’ etymologically, is the experience of something being beyond holding, that which outsizes our knowledge. And as that feeling of too-much-to-grasp lingers, it becomes wonderment.

When I think about what surprises me in these constricted days, what brings me a sense of great river plains and immeasurable skies, I realise—it is language.

The capaciousness of language, the way it arranges itself to surprise, is what poetry is made of. Jane Hirshfield, to me, is a master in this. She is both a poet of expansiveness and of surprise. Her poems are never large, but they also are:

The quiet opening

between fence strands

perhaps eighteen inches.Antlers to hind hooves,

four feet off the ground,

the deer poured through.No tuft of the coarse white belly hair left behind.

I don't know how a stag turns

into a stream, an arc of water.

I have never felt such accurate envy.Not of the deer:

To be that porous, to have such largeness pass through me.

Here, Hirshfield admits to a lack of knowing—how does a stag turn into a stream? And yet, like Mohanty, it is exactly that not-knowing she wants to inhabit. The confession takes us by surprise, then gifts us insight—she does not desire the litheness of the deer, but the eighteen inches between two fence strands. Not body, but space. Not matter, but its absence—the knowledge of what it is to be ample.

In an essay, Hirshfield calls surprise “epiphany’s first flavor.” She says, “It is the emotion by which we register shifted knowledge, in a poem, in life.” Her poem testifies to this. It tells us that even within the narrow, we can find expanses.

The wonder that a poem evokes—an abstract, hard-to-explain wonder—is elusive. Experiencing a sky is different from learning what causes that sky to be blue, then magenta. Hirshfield explains this difference astutely. She writes:

Science’s discoveries may—and do—raise wonder, but their usefulness does not depend on our astonishment at their existence. In art, though, this moment’s human response is the discovery.

Our involuntary response of being wonderstruck by elemental things—size, shape, texture—is perhaps an acceptance that upturns the logic of education and conquest. The acceptance that, like in a poem, knowing something does not mean we can say how we got there. There are places on the Earth where the sky is bigger.

Good heavens, because that is what you precisely start with and weave your way through this tapestry of words. A tapestry where the warps are your own thoughts about expanses, that dwarf us, humble us, breathe in us a sense of eutierria, whereas the words of Wordsworth, Mohanty and Hirshfield are the wefts, skillfully drawn through and inserted over-and-under with your own to create a beautiful fabric. All this while the loom is the readers imagination and our own personal experiences during this time, that hold it all together and create the necessary tension. Makes one yearn even more for the road.